On April 8, 2024, the world went black. For the first time in nearly seven years, a solar eclipse stretched from coast to coast of the US, its path of totality carving a track of darkness through the eastern part of the country. The WCHS hallways were bustling with chatter as students prepared to watch the sun go dark.

“A solar eclipse is when the moon goes in front of the sun and it blocks part of the sun,” WCHS science teacher Jonathan Lee said. “Because of this, we can only see part of the light from the sunlight, but a lot of light does get reflected off of the moon as well. So, we get that, you know, bright circle around the moon.”

Although Potomac, Md. was not in the path of totality, the area where the sun is entirely covered by the sun, the WCHS community was able to experience approximately 89 percent coverage at the eclipse’s peak. So, while the world did not go completely dark, sunlight was significantly dimmed, and a significant portion of the sun was cut out of view. The next total solar eclipse will be experienced in the continental U.S. in 2044.

“The next time there is going to be an eclipse in this area is in 21 years,” Lee said. “It’s not a once-in-a-lifetime thing, but this isn’t something you get to see very often. As a result, you get excited. Partially because it’s cool but partially because it went across the entire East Coast, and a lot of people got the chance to see a near-totality event.”

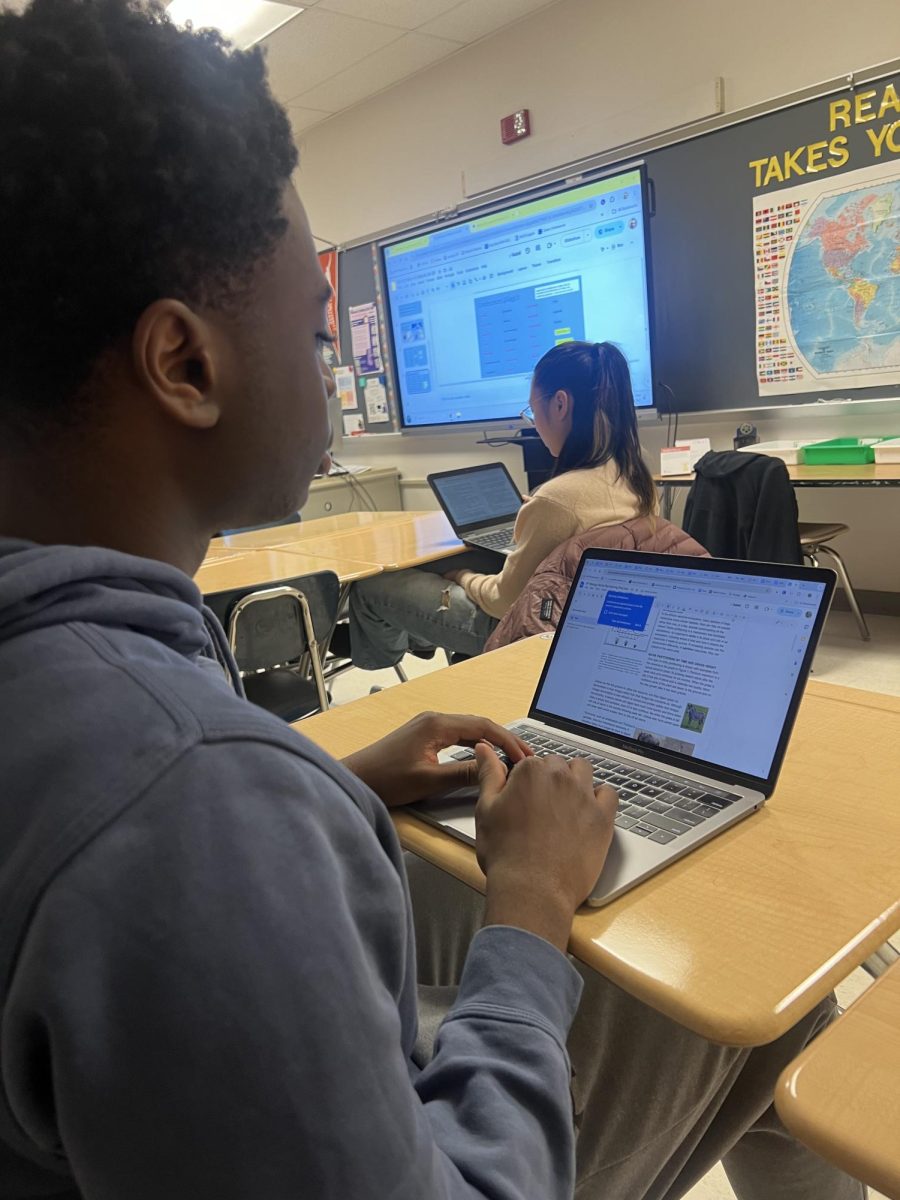

The eclipse’s peak did not occur in Potomac until 3:20 p.m., but the astronomical event began at approximately 2:04 p.m. when MCPS students were still in school. Many eighth period teachers allowed their students to go outside and join the millions of Americans gazing at the sky.

“It was super cool to see the beginning of the eclipse as well as the peak,” WCHS junior Morgan Branch said. “My teacher let us have class outside so we would look up every couple of minutes and see that the moon was covering a little bit more of the sun. When I left school, there was still a long time before the peak of the eclipse, so I was able to watch the coolest part from home.”

To watch an eclipse and gaze directly into the sun, one must wear eclipse glasses, mostly made of black polymer, a flexible resin infused with carbon particles. Viewing any part of the sun with bare eyes, even the slight part that isn’t covered in the totality of a solar eclipse, can instantly cause severe eye injury. For this reason, many students purchased glasses or were able to snag some from the limited amount being handed out in the media center.

“During the school day, everyone was asking each other if they had glasses to watch the eclipse,” Branch said. “Some people had enough to give to their friends, but some people weren’t able to get any, so they had to share with others when the eclipse started. I can’t tell you how many times someone told me to ‘make sure not to look directly at the sun!’”

Solar eclipses are unique because they are an astronomical event that sparks excitement in everyone, not just those who love science. Social media feeds were full of people discussing and explaining the eclipse, families reminded each other to use glasses, and teachers answered questions about what was happening.

“I loved that people were able to experience [the eclipse] in an environment where it could potentially be immediately explained,” Lee said. “I can totally see why our ancient ancestors thought this was magic of the gods. In other areas, not in Maryland, where it was actual totality, the daytime became nighttime, and it’s fantastic. I think it is cool to provide an environment where people interested in celestial stuff, like stars and astronomy, could see an event so close to home and have it be so tangible.”