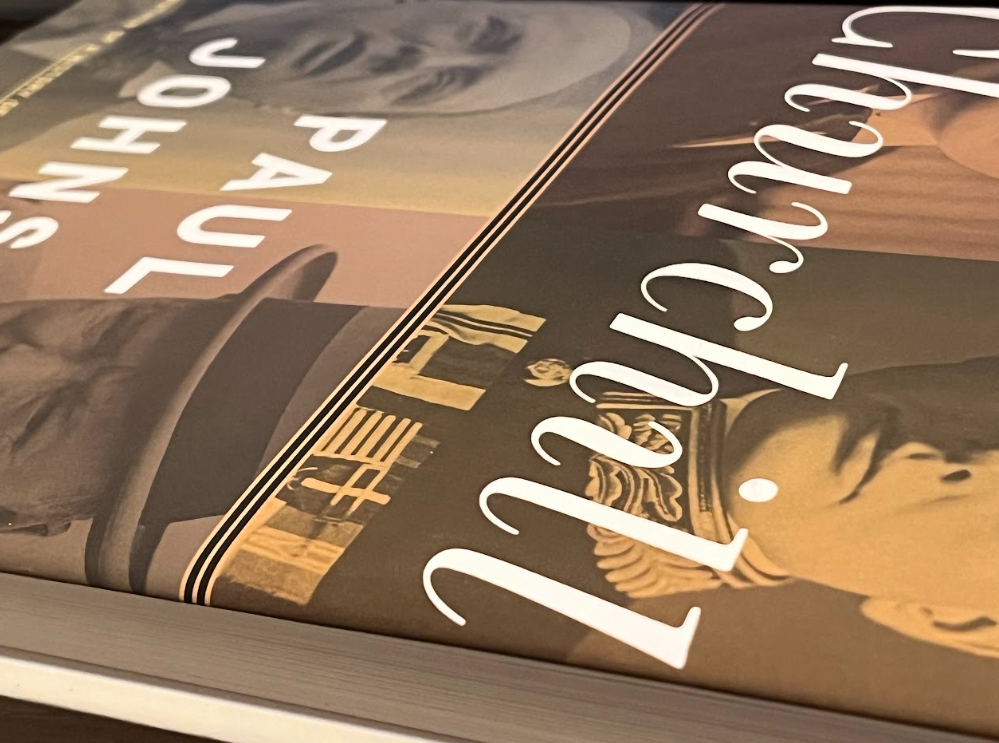

WCHS has quite the namesake. Every facet of the larger-than-life statesman was fascinating. Winston Churchill’s extensive list of biographers includes the recently deceased popular historian Paul Johnson, whose contribution, simply titled “Churchill,” is a short work that largely focuses on the man’s personality. While far from objective, the account is certainly worth reading. With less than 200 pages, it is not a hard book to find time for.

“Churchill” is in one way broad and another narrow; its subject is somewhat contradictory. It is broad in that it stretches from Churchill’s childhood to his funeral, but it is short and explains little. Johnson includes more interesting little details than significant events, providing a look into Churchill’s character rather than his repeatedly asserted importance. Exploring his personality is a significant part of what makes the book interesting, although it also renders “Churchill” less serious.

Johnson’s biography dives into Chuchill’s many hobbies as much as it discusses Churchill’s accomplishments in the House of Commons. Churchill as a writer, painter and bricklayer is placed front and center. The short book is also brimming with the interesting details that form one’s personality. For example, Johnson explains how Churchill enjoyed lighting cigars but only occasionally smoked them. Johnson also centers Churchill’s boundless determination and carefully planned speeches. However, he does not go into detail about any of those speeches, choosing to focus on the little tidbits of his personality instead.

Such a focus makes “Churchill” stand out. Including how Winston Churchill was an accomplished painter is fascinating but almost entirely irrelevant; ditto with bricklaying. With so few pages to spend, Johnson chooses not to focus on the impact of Churchill’s often controversial decisions, instead fleshing him out as a man. Churchill’s hobbies and interests show him as human. There are more serious biographies with more material content, but this side of the figure is important too.

However, “Churchill” does briefly cover its subject’s many accomplishments. A good chunk of the book is devoted to Churchill’s role in the House of Commons, placing characteristic emphasis on his personality. His speeches are described as well thought out and humorous, but Johnson does not go much further than descriptions. They are not shown nor examined; with less than 200 pages to fill, “Churchill” feels incomplete.

The book has another more striking flaw. “Churchill” makes its purpose clear; from the very first sentence, Johnson sings the praises of the man who lent WCHS its name. He begins the book by calling Churchill “the most valuable to humanity, and also the most likable” figure. He is presented nearly as a paragon, and it reads as much like a myth as a history — the epitome of the “great man” worldview.

It is still an interesting read, though Johnson’s unerring praise contributes to its feeling of incompleteness. Though far from flawless, Paul Johnson’s “Churchill” is worth reading.