Sumthing’s off: MCPS math levels decline

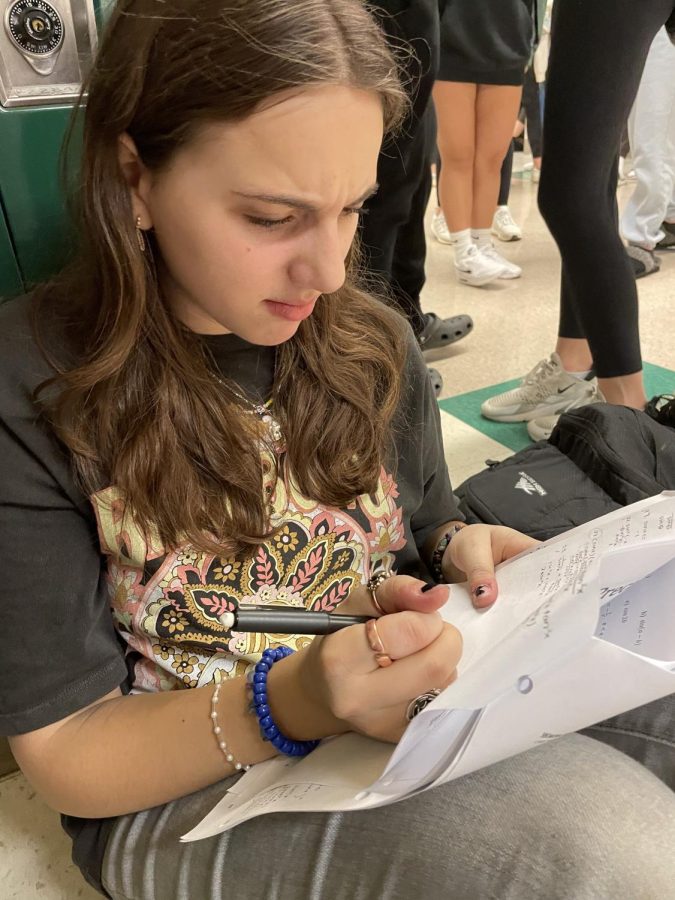

WCHS sophomore Julia Bloise does math homework during lunch in an effort to relearn Algebra I concepts that she learned during virtual school.

March 23, 2023

Starting in Kindergarten, students are continuously learning basic math concepts that allow them to move forward and comprehend more complicated ones. Multiplication and division lead to fractions and percentages. Algebra leads to trigonometry and then calculus. For years, this progression has moved students from primary and foundational concepts to complicated and hair-pulling logic. But what happens when that progression is interrupted and students are forced to skim or skip an entire year of math?

In late January, Maryland released the results of the Spring 2022 Maryland Comprehensive Assessment Program (MCAP), which shows that virtual learning continues to have a devastating impact on students’ ability to learn math. The MCAP exams test students’ math and english language arts (ELA) learning proficiency. Following the national trend of decreasing proficiency levels in math after virtual learning, only 22% of Maryland third through eighth graders scored “proficient” in math, 11% lower than the 2018-2019 school year, the last time the test was taken. Similarly, 31% of third through eighth graders in MCPS scored “proficient” in math.

“Learning during virtual was a lot harder because you were at home with so many distractions,” WCHS sophomore Eva Linder said. “Also, it was a lot harder to learn because it’s hard to pay attention to teachers who are a little box on your screen.”

As school transitioned back to in-person learning last year, students were expected to continue with the next level of their progression, just like any other year. In a typical year, classes would begin by reviewing some key concepts that might have become foggy over the summer, but last year it quickly became apparent that these concepts were not just foggy, they were never learned. Missing past mathematical concepts hinder one’s ability to learn new ones, and it still affects students today.

“It was harder for me to learn stuff [during virtual learning] and I didn’t really fully understand it,” WCHS sophomore Julia Bloise said. “I’ve noticed that this has really impacted me this year because it’s really hard to remember the foundational stuff that I need for Algebra II; it’s just not coming to my brain. The teacher always says we should remember certain concepts but I don’t because we learned it all virtually and half the time my connection was bad or I wasn’t paying attention.”

Typically taken by WCHS students in middle school, Algebra I is the first high school level math class in the academic progression. Introducing algebraic concepts and logic sets the groundwork for all future math classes, yet only 20 percent of MCPS students scored proficient on the Algebra I test last year.

“I teach Algebra II and the kids who are taking this class this year were virtual during Algebra I. We saw the effects [of virtual learning] last year and it’s still having its ripple effects this year,” WCHS math teacher Beth Meyers said. “Every student is going to have different gaps. We are having to go back and reteach things, or students have to go back on their own and make things up on their own. In Algebra II, we spent a while going back and reteaching Algebra I concepts at the beginning of this year. We kept having to insert Algebra I into Algebra II.”

Although the results showed a decline in math proficiency, ELA proficiency levels are back to pre-pandemic levels. According to the report released by Maryland, “the decline in middle school math proficiency rates was 3-4 times larger than the decline in ELA.”

“Math is a progression. If you miss one year of math, it is so much harder to learn new math because you don’t know the foundation of the new concepts,” Bloise said. “You also start learning English when you’re young, but it’s something that you have to constantly use in your life, so it’s so much easier to catch up. Also, we do similar things every year so even if they introduce new concepts, there isn’t a foundation that is missing.”

While the county has not disclosed whether they have a specific plan to solve the pandemic learning gap, it is abundantly clear that it will continue to impact both students and teachers for years to come.

“It is clear that the pandemic has resulted in a significant learning disruption over the past 18 months,” MCPS Superintendent Monifa McKnight said last school year. “This is really going to require being intentional and direct to know each learner, to know what their learning needs are and address them. That has to happen in every classroom, with every child in this system. That’s what we owe them.”