Once upon a time, learning proper cursive was an essential part of any school curriculum. However, in modern days, it has become the exception. Only 21 states now require school curriculums to teach cursive in some capacity, and it is not enough. The benefits of teaching cursive are many, from the positive mental effects to extending the lifespan of a dying art form. In contrast, the so-called detriments to such initiatives are tenuous and a sad symptom of over-digitalization.

The positive effects cursive can bring to students are often understated but are important to institutions whose goals are to reinforce education. Many studies, including recent ones from brain scientists at the University of Indiana, prove that for students, particularly elementary school-aged children, going over the alphabet in a second form improves memory and aids them in grasping a firmer comprehension of the structure of words. Learning to write cursive improves fine motor skills, engaging an area of the brain not stimulated by print writing. In fact, learning cursive could help students who suffer from certain disabilities: students with dyslexia can sometimes struggle with reading and writing in print due to the similar shape of many letters. Cursive letters, however, possess further differences that can help certain students decrease dyslexic tendencies and further their abilities.

Brain development is already enough of a reason to revitalize cursive. Still, there are further practical benefits to its study; most basic legal documents, including checks, require a cursive signature as an endorsement of validation. If schools aim to prepare students for life in the adult world, should helping them be confident and successful when working with legal documents not be a part of that?

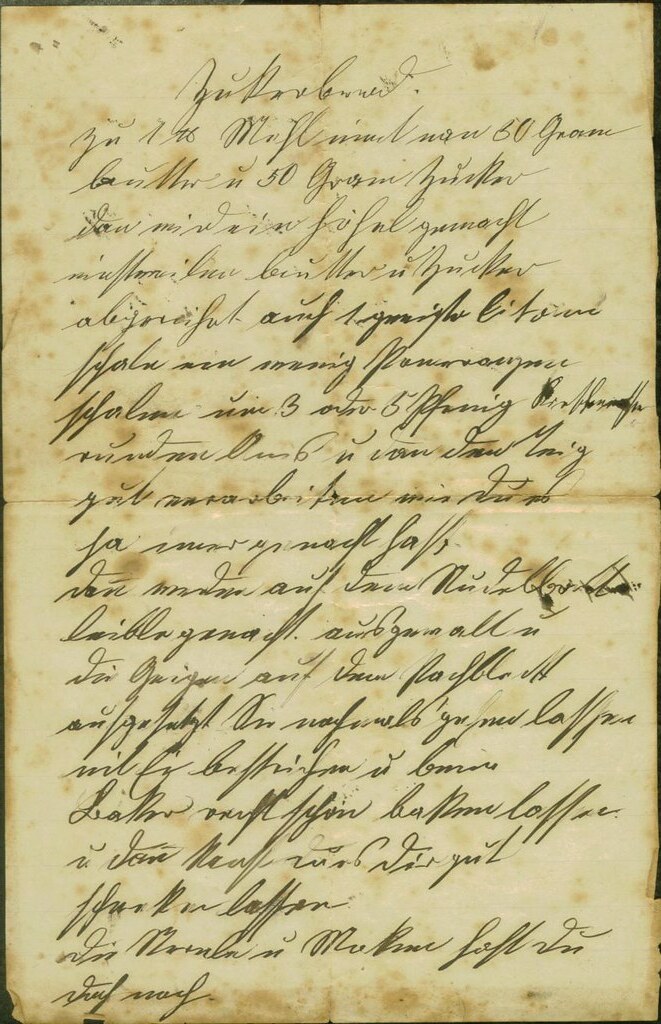

On a more sentimental level, learning cursive is essential, even if only to keep it alive. Cursive writing is its own art form, and a dying one. Besides engaging the brain in ways regular reading and writing cannot, cursive claims another crucial role in historical documents. Leaving students unable to read cursive robs them of a unique reading experience in many old writings, including America’s founding documents. Granted, many of these historically significant works have been copied into print, but what about more personal documents, say, letters from grandparents and great-grandparents, many of whom still write in cursive daily? Even in the name of sentiment, students should be allowed to understand cursive for themselves.

Students are not the only ones that benefit from the study of cursive, particularly in schools: teachers, who long have struggled with poor handwriting from students, would be able to read and thus grade handwritten work with considerably more ease should students be able to transition to a standard of cursive writing. And although the digital age is reducing the need for handwriting efforts, learning how to communicate through effective written language builds discipline, focus, and confidence.

There are those who claim cursive is an archaic form of communication, and the rapid advancement of the digital age has rendered the art of it obsolete. As was just proven, they could not be more wrong, and when you apply that same logic to a more obvious art form, it is easy to see how. If the advancement of technology meant humans didn’t have to bother practicing “obsolete” forms of art, what about painting? Or sculpture? Artificial intelligence can already produce in seconds what would take most people at least hours. Yet the use of AI to create art has remained a source of great controversy. The debate around cursive should be no different. Just because technology can does not mean technology should, and just because technology can does not mean we should not.

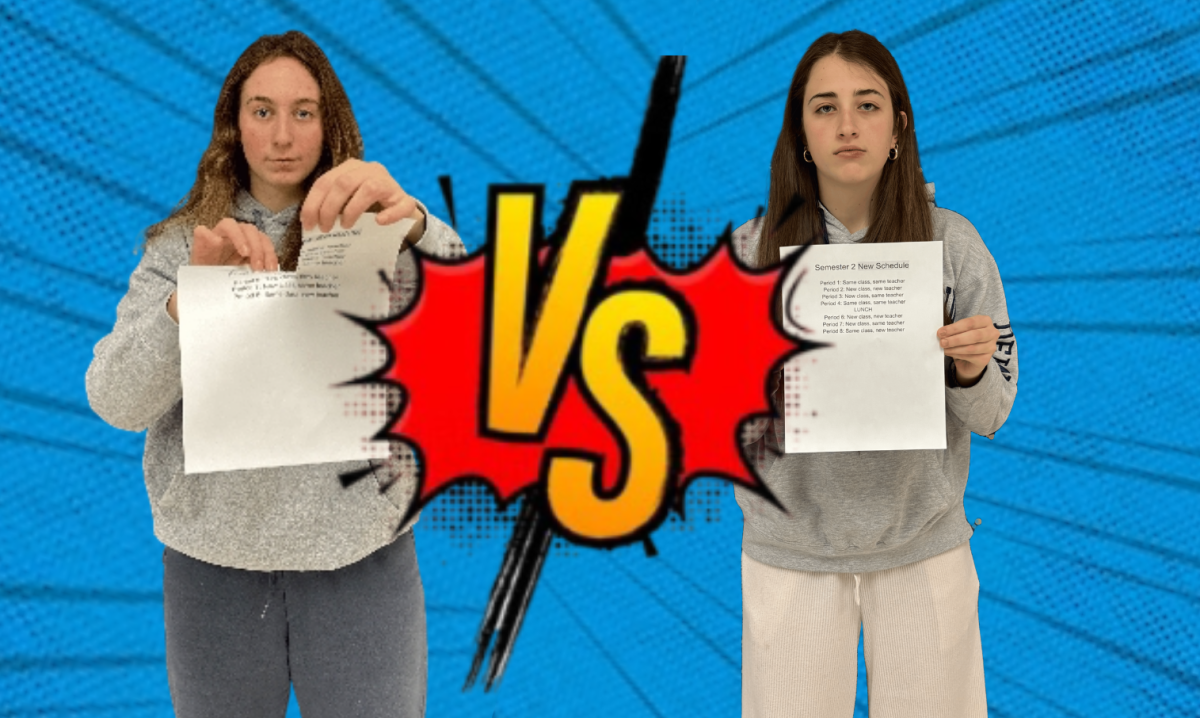

It is also claimed that teaching cursive would take resources and money from other valuable learning initiatives. However, that is under the presumption that teaching cursive requires entirely new courses, teachers, and a system overall. Cursive can be, and has been, implemented into basic English courses. Relegating or compressing other units and topics in English would free up all the resources needed to effectively teach cursive as part of the curriculum. Certainly, creating a new elective course would be difficult, and would require long deliberation and debate and construction, but embedding cursive into existing English courses as additional units would be much more simple, as well as bringing all the benefits of cursive into a mandatory setting.

Simply put, the numerous and powerful reasons for teaching cursive in schools far outweigh any meager reason not to. The world is becoming steadily more technology-dependent, but that is not always good. Cursive is the ultimate example of staying rooted in humanity – if humans lose art, what keeps us from being robots?