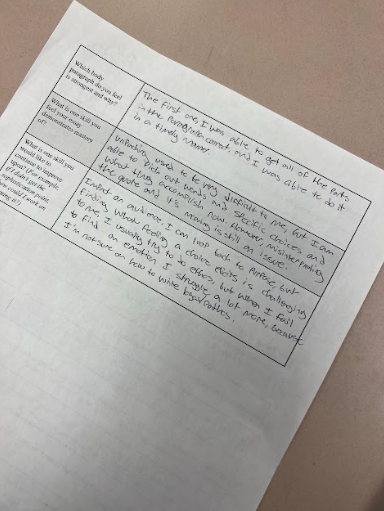

Chromebook screens illuminate dark rooms. Canvas pages open on every screen. Assignments are being worked on in Google Docs. Computers and the internet have been integral to MCPS classrooms for years. As digitization increases, students will naturally adapt to this new medium, and older skills, such as cursive writing, will fall out of relevance. So why should MCPS obligate its students to learn this time-consuming and pointless craft?

Today, computers are the beating heart of a functioning school. Teachers post assignments, contact students and attend meetings online. Students check their grades, take notes and do research online. Most classes have adapted their curriculum to utilize the internet, with Science classes doing labs digitally on PhET and math classes posting homework on Delta Math. Even English classes, which bear the responsibility of teaching cursive, post many assignments online. As a result, students rarely have to physically write anything, and when they do, they can quickly get by with simple print writing. The speed and efficiency of cursive provide little benefit when students only have to write a few sentences at a time.

Additionally, cursive is a skill, meaning students must keep their knowledge fresh. Because assignments are frequently online, students have little opportunity to practice their handwriting and can eventually forget cursive altogether. Schools need more incentive to teach students a skill they will seldom use and likely forget.

Teaching cursive also costs a lot of time and money. Proposals across many states would cost taxpayers millions of dollars to teach the practice. Costs also balloon past projections. According to Center Square, a local news outlet based in Michigan, a proposal to mandate cursive education in the state was estimated to cost eight million dollars after initial estimates said it would cost five million.

Even more importantly, teaching cursive takes away class time that could otherwise be used to teach more valuable skills. For example, touch typing, otherwise known as keyboarding, is incredibly important in an increasingly digitized world and, according to a study by researchers at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, can assist students, especially those with disabilities, to reach similar speeds as students who handwrite. However, touch typing can only reach its efficiency if proper care is put into teaching students proper techniques, which cannot be done if a school’s time and resources are wasted teaching less valuable skills, such as cursive.

Even outside of school, there are few useful cases for knowing how to read and write cursive. Most documents are digitized, negating the need to understand different handwriting. A lot of work today is entirely online, and the value of the internet and computers, as well as the ease of adapting to their use, was seen when COVID-19 shut down the world. Cursive writing is explicitly expected only with signatures, yet with the prevalence of e-signatures, which do not require stylization, cursive is increasingly irrelevant.

Proponents of teaching cursive in school also argue that its past use would require younger generations to understand it; most historical documents would only be legible with knowledge of cursive. Communicating with older generations, who were taught to write everything in cursive, would only be easier with being able to read what they write. However, with the recent advent of reliable AI tools, deciphering texts and letters written in cursive would be even more accessible, and in cases where technology cannot solve the problem, cursive can be taught in college or other higher education institutions.

With the prevalence of the digital age, schools must look to the future and prepare their students with skills that are more useful in their upcoming lives. The costly and time-consuming process of teaching cursive will not yield long-term results for students and will take resources away from more important topics. It is in the best interest of students and schools alike to leave cursive in the history books.